A girlfriend brought me lunch yesterday since I still can't drive. We've known each other since our kids were babies, I suppose almost twelve years now. Over soup we talked about everything from work to our health -- we both had a rough 2015.

"You know," she said, "it's true. You don't realize how when you have your health, you have everything, until you don't."

Yeah.

We're young-old, both in our early forties, still running (when not sidelined by said health), still trying to eat healthy. Nobody's thrown in the aging towel or anything. But suddenly in the past few years, the conversations of our friend group have morphed from potty training to WTF did I really get tan lines on my forehead wrinkles? Initially, the talk was more that of shocked realization -- the first discovery of a gray hair, the first mammogram, the first night sweat.

I think we're in the anger phase now.

And I wish I were more tranquil about it.

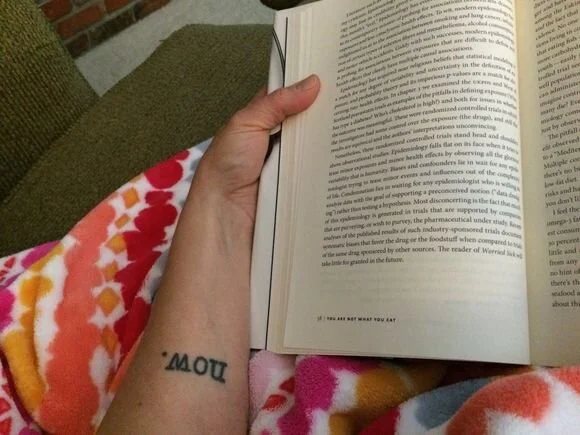

It's true I've been dying since I was born, that's the way it goes, circle of life. The problem is that now I realize it. My hands on the keyboard wear the same wedding ring but they aren't even remotely the hands my husband held at our wedding in 2001. I remember at the time looking down at my hands and wondering what they would look like when they started to age.

And now I know.

Last night I was trying to explain to my mother, who is here driving me to appointments while my husband is back to traveling for work, what I've learned about getting up off the floor with a broken leg.

"You have to flip over like a bug, then you get on your knees and you can get up that way."

"But when you're my age, your knees hurt, too."

Oh.

I get so much of my personal happiness from moving my body. This broken leg has taught me how much I value my physicality, the feeling of movement, the deep breath of air needed for a big push. My personal agency, my ability to get myself from point A to point B without help and without pain.

I'm so mad about getting old.

I'll look back on these words when I'm 62 and wonder how I possibly could've thought I was old now. I will and I won't. Right before I burned my journals from my twenties, I read them, and I didn't laugh at that girl. I understood her, I remembered her, in some ways I pitied her because she was really unhappy and anxious and still a little bit ill. And she really hated the body that worked so well at the time.

Is it too much to have a healthy body and a wise mind at the same time? It must be, because that's not how it works. As the body falls apart, the mind realizes its worth.

My dad told me he watched a documentary about Alzheimer's and they said to make a recording of all the songs you loved when you were young and give it to your children. Then if you get the disease the recording will flip a switch and you can enjoy the long-term memories.

Then he told me what to put on his.

His mom died of Alzheimer's.

I told my mom as she stared at the saddle we got for my daughter that I couldn't remember saying goodbye to my horse. She told me I was there, that he walked willingly into the trailer of the buyer. I'm sure I cried at the time but sometimes I think it hurts me more that I can't remember than whatever I felt at knowing he was leaving my life due to my own choices, because I wanted to be a normal teenager and not someone who came home every day to muck out a stall no matter how much I loved my pretty bay.

Is it winter? Is it the broken leg? Is it the January of pop culture death? Is it my daughter preparing to leave elementary school? Is it my helicopter daughtering of my aging parents? Is it 27-year-old Adele singing about when she was young? Is it seeing Princess Leia look like a grandma?

Why am I suddenly so mad about getting old?

Is it because I secretly believed if I just kept running my face and hands might age but my body would work right until I dropped dead ... and then suddenly I couldn't run anymore?

When I was a kid, I believed that once you turned forty, it was over. You gave up, you stopped wearing makeup, and you settled into the Barcalounger with the remote and Lawrence Welk.

When I was in my twenties, I started seeing more and more seventy-year-olds sailing and running and skiing. They seemed like they looked younger, too, probably because they were wearing jogging suits instead of polyester pants and nurse shoes. Collectively, Americans seemed to stay younger longer when those damn Baby Boomers refused to go softly into the dark night of middle age. I got excited. I bought in: I'll just stay young, then.

Now I'm not sure how you're supposed to get old. It doesn't seem as clear-cut anymore now that Harrison Ford is one of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood in his seventies but Peyton Manning is washed up before he's forty. What's old? What's young? What is the standard to shoot for? Do we die in harness, can we retire even if we want to? Do we prepare mentally to work until eighty or live on a fixed income and eat cat food at sixty-seven?

Damn, I'm so mad about getting old.